The Experience of Dying Teaches you to Live Well

Rakesh Shukla explains how he conquered the fear of death, to live a better life

A few weeks ago, I discovered a growth/tumour on my lowest right rib. Painful to touch. I was having a haircut when I first felt it. I finished the haircut then called a friend who is a doctor. He put me onto his friend, an onco-surgeon. When I reached there they were surprised when I introduced myself as the patient. The test would return in a day and the damn thing was benign so that was a good thing. What wasn’t was that it was growing and hurting more day by day.

But that one day and night forced me to think of many things. Of living with cancer. Surviving. Or not. Of death and dying. But for the longest time, these seemed as operational problems, not scary ones. For a little scared boy, how did I get here?

Tryst with death in childhood

My childhood was spent in hospitals. I had rheumatic heart disease very early in childhood. Survived a heart attack early in my life. Have suffered brain disease and arthritis for years. I live with two blocked carotids. I’ve broken my back and some days, it just gives way. None of those things is near dying though. That is when you know you have a few seconds, and only a few, and then the lights will be out.

I was not just sick, I was a very scared child. I was scared of pretty much everything. Including dogs. But I remember hating this feeling, and wanting to be brave. My parents wanted to shelter me to the point that none of my ‘conditions’ would be spoken about. The constant living with needles and incisions gave me a tremendous capacity for pain. And to prove myself a man, I’ve done some extreme things, but that’s a story for another time.

The days and nights at home, in hospital wards, in ICUs, in ICCUs and neuro-surgery, I remember thinking what would it be like to die. Not what happens after when you die, but the moments leading up to when you do. Does your whole life flash in front of you? Are you scared shitless? Do you have regrets of unfinished business? Do you feel sorry for yourself that it was worthless? Are you brave and you smile because it was a good fight?

I have seen people die. Some I loved. I have seen the fear in some eyes, acceptance in others. I have retrieved bodies from autopsies. I’ve cremated them. I remember never feeling emotional about it but saw it with a detachment. I also know nothing in life is the same as till when it happens to you. If you live long enough and dangerously enough, and most of all if like Siddhartha/Herman Hesse said, “Find truth your own way,” you face the moment of death and knowing who you are.

Cliff-hanger

The first time was I was about 5 or 6. In Shimla, we lived on the top of a hill called Craigdhu and there was a small field where we would play. On the far side was a wall, and the other side of the wall a few hundred feet down there was a sliver of a road, beyond which the hillside continued. We all knew not to cross the wall.

Each time someone hit the tennis ball we played cricket with, and it went over to the other side, the game was over. Those times were not like today — you had a ball you made it last a year. So on one day, the ball went over and the game was over. But I decided to climb the wall and I could see the ball about 15-20 feet below. My friend Shekhar Kapoor aka Dimpu kept telling me not to, but I decided to cross the wall. It was the only time he left my side.

After the first few feet, it was a steep downward slope covered with dry pine leaves. And I slipped. My head was clouded by panic the first few seconds then it became very quiet. I remember not screaming because there was no one to help. I remember seeing the road I was going to fall on and death rushing towards me.

I remember telling myself to try and hold on to something. I spread my arms and caught the first clump I hit and held on for dear life. And I stay still for a while. But there was the job of climbing back up. When I finally reached the wall it was getting dark and people including my father were calling my name. I never told anyone what happened. I developed the habit of standing at the edge of heights. It helps control the fear and the thrill is still indescribable.

You don’t think about it then but you know the feeling and impression it leaves you with. I learnt that it is OK to be scared but it’s essential that you don’t panic and that most of all when chips are down you are left by yourself. And you can never give up — I was lucky I had not fallen but I still had to climb back up.

Overcoming fear of drowning

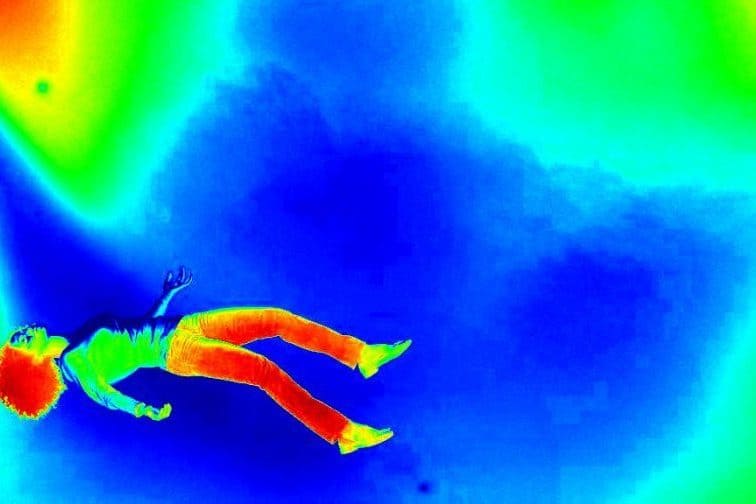

The second time came about 20 years later. I was about 15km upstream of the Ganges, at Rishikesh, and I fell off the raft just as it hit a rapid. As I got sucked in and the water closed over me it was sheer panic. When I came back up, it must’ve been a few seconds but it felt like minutes. Everything then was in ultra slo-mo.

I realised my helmet was gone and my watch was going to come off! I clasped the watch with my other hand. And I screamed as much as I could — but you can’t — I took in more water and realised that to survive this I need to focus, steer and not hit any rocks with my head. I saw the rafts recede at a distance as I raced ahead. I was picked up about a kilometer downstream in an eddy. The next year I returned, and before we came to the same rapid I jumped off the raft myself. I had to learn to control the fear of drowning.

A narrow escape

The third time was about two years after the second. I was cycling alone from Manali to Leh. As I crossed the steep hairpin sections between Palchan and Marchi, I was being covered by Star TV’s crew for a travel program because they couldn’t understand this loony man was going up alone, when the few cycling crews were coming down. The anchor asked me why I was going there. I said I don’t know really, but because it’s there, and because I needed to find myself.

This was at the end ofApril-early May and Rohtang was closed. When I reached the checkpoint past Marhi the army man allowed this loony man on a bike, a bunch of Israelis on Enfields and a lone American on foot. I got caught in a snowstorm as I was about to reach the top, and would not climb down to Koksar in the night so I had spent the night in a tent on a snow-covered field at the top of Rohtang La.

After the uphill of the last few days, I was making great progress coming into Keylong from Koksar and I was just short of the confluence of Chandra and Bhaga. So as I went steeply downhill en route the next destination, I saw one stone, the first one, fall in front of me. It was like a hailstorm of small grit-sized stones. I looked up — rock slide.

I could have turned back and gone about 50 feet up to a clearing but it was a steep 50 feet and it could be too late. Or I could go downhill about 300 feet, but miss braking on the steep twisty path and go down into the river before being hit by a boulder. Or both. I went downhill. By the time I cleared that section and stopped to turn back I could see the road covered with rocks the size of tennis balls and small cars. I had discovered Shiva. But that is also the story for another time.

Tiny creature, severe implications

The fourth time was 10 years after that. I was in the boondocks in Kerala. It was late evening and Helen and I were the only guests in this ancient and luxurious lakeside home. A large ant bit my toe. First, I started coughing, like a dry cough. A few minutes later, I started feeling itchy and was breathing heavily.

I realized suddenly that it was an anaphylactic shock. I would not die not from the allergy or anything, else but from chocking. The nearest hospital was in Alappuzha if we could make it. There was no Google Maps at that time and I knew I did not have the 30-40 minutes. I told Helen to empty every antihistamine tablet on the bed (which I carry for my numerous allergies including to dog dander). Then I had to take them one at a time but I could hardly swallow by now. I must’ve taken 15, forcing in one at a time. Then I lay down to force myself to breathe even as there was a melee around me. In a half-hour, it was like it never happened but for the thick rash that covered my body.

Build a well-lived life

Are there any lessons in facing death? One is, it’s nothing to be scared of. No matter how you look at it, it’s a change of state. I worry every day about my hundreds of children but I also know about the hundreds who wait for me when I go across.

I have learnt that some qualities I love the most in people — such as character, valour, controlling fear, being calm and collected — I had none of them to begin with. But they all can be acquired. I learnt that I do not have the fear of dying that I have seen in the eyes of so many; in the very last seconds, I do not have the dissonance of having been worthless. Unfortunately, it has shown me the other side of me that I am not proud of. The great impatience I feel for those who do not try to control fear or pain. It has caused me the loss of many folks I otherwise valued.

If you have made a real contribution to the world, you can smile when the lights go out. If you haven’t, now is the right time to start. The experience of dying, most of all, teaches you to live well.

Stronger with RAKESH SHUKLA™ is a framework for developing unparalleled mental and physical toughness. It is based on Rakesh’s life, and has helped drive two ‘comebacks’.

Rakesh Shukla slept on railway platforms on his way to creating a world-leading technology company — TWB_, which is the choice of over 40 Fortune 500 tech customers worldwide including Microsoft, Boeing, Airbus, Intel, and others. However, at 43, he lost everything within a year. Alone and friendless, he spent the next five years repaying over INR 20 crore of debt and taxes, while building back his company and reputation, and creating and funding VOSD — world’s largest dog sanctuary and rescue.

Rakesh Shukla has suffered heart disease since he was seven years old, had had two heart attacks by the time he was 30, suffers from brain diseases, has broken his back and his kidneys are failing. Towards the end of this five-year period, Rakesh weighed 88 kg and very unfit. Today, at 48 years, he can lift well over 100 kg above his head, run a 10-minute mile, do 2,000 push-ups, and 250 pull-ups. He has never been to a gym, been on a diet, had a trainer, or taken any supplements.